People enjoy watching artists work much more than I – as the one working on a project – expect. Mostly I see artistry as an acquired skill, and a matter of how well the eye is trained. Natural talent is great and all, but it only bears fruit because we put thousands of hours into it.

Yet there’s a mystery that surrounds the creative process, perpetrated no doubt by artists themselves. We hear of impoverished, tormented artists – isolated for the sake of their art, alcoholic and depressed. We hear of artists working through the night in fevered inspiration, or lying in bed for days unable to lift paintbrush to canvas, slaves to a fickle Muse. Perhaps an idea comes to them in a dream; perhaps they work in a trance-like state and awake to find they’ve painted a masterpiece.

No doubt some artists live such dramatic lives. It’s true that a bit of personal strife adds zest and poignancy to art. But it isn’t hardship that creates the art; the art is created despite hardship, and that’s the only merit I see in artistic misery. I think the majority of artists live much more balanced lives than the dramatic examples that make up our idea of them.

I live a pretty comfortable life. When I’m self-centered, isolated, and financially insecure, my art suffers. When I make time for connection with others, when I look outside myself to contribute to my community, and when I have just deposited money in the bank, that’s when I’m prolific: that’s when the art flows into something beautiful I couldn’t have imagined would come through my fingers.

All that said, artwork doesn’t leap fully formed onto the page. It’s a lot of hard work: 90% of the bulk of medium on the page will look nothing like the final picture; it is only in the last few days and hours that the magic happens and a picture looks like it’s supposed to. There is an element of magic, when my eye clears and I see exactly what must be done to make everything right. I never know when that will happen, which means that every piece of art is a practice in faith: I am going to trust that, if I just keep labouring, in the end this will work out, even though I don’t feel like it’s ever going to.

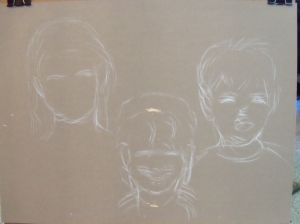

So perhaps this is dangerous – I don’t want to demystify the process too much! – but I’m going to take a portrait that I completed in late November, and let you watch me work on it.

It began with photos in September. As usual, I picked a primary photo of each child’s face to work from, with three or four secondary photos to inform me of things that the primary photo might not capture about the child.

Here I’ve printed out cheap versions of the digital image onto paper. Hard photos are much crisper to work with, but digital is important for playing with sizes, for lightening dark shadows so the artist can see what’s going on. The kids’ Mom, who commissioned me, liked photos of them standing in the garden, so I played around adding different photos onto the background. Notice how small the faces are in the frame: I didn’t at the time want to keep printing out new versions and getting the sizes all right. This mock-up is not by any means a scaled version of the original. That backfired on me, but at the time of this photo I was optimistic and confident in my ability to fudge it.

Notice also that the faces each have different quality and directions of light. This makes tons of extra work for me, but it can’t be helped. The boys’ pictures capture so much of what I want them to be, that I wouldn’t sacrifice that for uniform lighting. The girl’s face . . . well, it wasn’t quite what I wanted, but I had to get started. I ended up changing her picture four times throughout the process.

Wow, aMAZING! Can’t you tell it will be wonderful?

Usually, I grid each picture into 16 rectangles, both on the mock-up and on the paper I’m working on. This time, since my mock-up was approximate, I didn’t bother. Bad Ayisha. Bad bad bad. That has just added another week onto my work, but I am blissfully unaware of it. When I plan carefully, I have a clear direction going forward, so that future decisions barely seem like decisions at all. Poor planning means that I’ll have to feel out the picture, constantly hedging my decisions against each other, guessing and testing until it starts to look how I want it.

The Background

I usually put background down first. It helps me see the shape and placement of the people, and I can get a base of pastel down without messing up faces I’ve spent time on. Here, I draw the flowers white to experiment with placing, and to make it easy to add colour on top. First time I’ve tried that with pastel. I think it was unnecessary.

One problem with showing people art while it’s under construction is that the undiscerning or kind say “Oh, that’s nice” . . . (a blow to the ego, because I want them to see how much better I can actually do) and the discerning or critical start critiquing it (an outright attack, because my eye already knows what’s wrong – I just can’t work as fast as my eye). That’s something common among artists: we become petulant and our egos are more easily injured in the middle of art that isn’t going how we want it to.

At this point, I’m thinking, “How will I get so much colour to tie together?” and, “I can’t stand that row of pink flowers by the older boy’s head. I know it’s because I keep changing the placement, but it’s UGLY!” I have very little patience with ugliness, which is what both drives me to finish art and hinders me from completing it.

A few days later:

The Zombie Family

There’s a little old lady standing in for the girl right now, unfortunately.

I have very kind girlfriends whom I trust, so I watched Foyle’s War with them while I worked at this stage. If I didn’t know they would still like me anyway, I would never have let them witness this.

I often “watch” movies while drawing. During the long middle, which is the bulk of the process, distraction helps. It gives my thinking brain something to pay attention do, while my eyes and hands can be busy. The critical track in my head gets partly drowned out by the movie plot. It’s like turning on a fan in your room to soften the sharp sound of kids shrieking in the other room while you’re trying to sleep.

Did I mention it was going to get worse? Can you imagine if the kids’ Mom walked in while I was working?

The littlest is starting to look like himself, but the girl looks bearded. The problem at this juncture was that, since I changed the photo I was working with, I had to brush most of the pastel off of the girl’s face with a stiff-bristled paint brush. But even after brushing it off, the new pastel I laid down kept smearing. I’d put a pastel stick up to her face, and things would happen I couldn’t control.

That is why Krylon makes this wonderful thing called Workable Fixatif. I held off using it as long as I could, since I didn’t want it to affect the surface of the other faces, but when I finally applied a few coats, I got a new surface for the girl’s face. But I’m getting ahead of myself. First:

The older boy looked proportional to begin with, but about two weeks in, I realised something had gone terribly wrong. I compared photo and pastel, trying to interpret what had happened. The angle of the neck was all off. The proportions in the face were wacked. I tried to reassess, to hold the photo up close to my eye and compare them at the same size, then correct the mistakes. . .

. . . but he just started looking like a teenager. I don’t know if you can tell, but there’s too much length in the eyes-to-nose-to-mouth ratio for a kid his age. I wondered if I was going crazy, losing my touch. I was also upset, because the kid is so cute, and I was uglifying him.

And then a week later, it came to me. I had accidentally switched key photos. In the twelve or more photos that I kept sifting through with my cleaner hand, there were two that were similar – no doubt taken within minutes of each other – but the expression is different, and the face is tilted up and turned more toward the center. Most of all, the way the head joins the body is drastically different.

I switched back, uncorrecting what I’d corrected. It was annoying, but I was so relieved to find out that there wasn’t something terribly wrong with my mind-eye connection that I didn’t really mind. It just added time, and since this was to be a Christmas present, I didn’t have a lot of that.

Thanksgiving day, surrounded, supported, and distracted by family, I found the whole picture coming together under my fingers. I began to feel the beauty of the dusty pigment in my hands crumbling onto the sandpaper.

I didn’t like my primary photo for the girl, so I switched again, leaving the hairstyle and this time working from two photos equally, which I don’t usually do.

What a relief. Looking at the above picture, it looks like cute kids. Doesn’t look like them specifically, but not being faced by zombies makes drawing a lot easier.

Sunday the magic happened. I finished things up Tuesday. Somehow I failed to get a photo of the final product, but here’s the pastel mere hours from completion. (The only way I can tell the difference between it and the final one is that I had signed my name in black, and then a little later I rewrote it in white):

Ta-da!

It’s a bit busy with all that colour, but I tried to balance it out. The red in the apple is reflected in the red amaranth behind the girl’s head, etc.

In the initial photo taken in the garden, there were white flowers in front of the girl, and I added those back. I wanted to create a circular motion, so that the eye would have an order in which to look at an already-busy picture. One reason a portrait of three is a challenge is that a good work of art needs a focal point, yet with three kids you want each of them to be the focal point, otherwise one might look more loved or more important than the others. Our eyes go first to the place of greatest contrast – the youngest’s face – so I wanted to draw the viewer’s eye next to the older boy, then to the girl, and then have their eye travel back down those flowers to the youngest. Perhaps the attempt was successful, perhaps not. I don’t yet have perspective on that.

It’s fun to revisit the process. There is much angst and drudgery involved in art, but it’s a good challenge too. In the end, if the picture hits the magical sweet spot, it’s easy to forget the pain involved in birthing it. I still maintain that art need not be agony, but I have to admit that there are times with any artist when clarity of sight eludes us, and we can only pray that the final product is satisfactory.

Copyright 2010-2011 Ayisha Synnestvedt. All rights reserved. Artwork images at this site may not be duplicated or redistributed in any form without express permission. If you would like to use images from this site, please contact the artist for permission.

4 comments

Comments feed for this article

April 9, 2011 at 5:09 am

Amanda Rogers-Petro

Ayisha — I enjoyed reading this and seeing the progress of your work so much! Thank you!

April 9, 2011 at 12:11 pm

Lori O

WOW!!! How absolutely fabulous! Thank you for posting this.

June 26, 2012 at 6:14 pm

Mica. C.

I started out looking for Maxfield Parrish prints and ended up here. I don’t know if you consider that a compliment or not! Your work is intriguing very international

June 26, 2012 at 10:48 pm

aysynn

The more I look at Maxfield Parrish’s paintings, the more impressed I am with his work. Well worth getting prints of! Hope your search was successful; I’m glad you stumbled across my website in the process.